“I found Rome a city of bricks and left it a city of marble.” This boastful proclamation is attributed to Caesar Augustus, the founder of the Roman Empire. But how truthful is it? Did Augustus really transform The Eternal City from brick to marble? Diane Favro, a professor in UCLA’s Department of Architecture and Urban Design, is using digital technology to answer this question.

La Dolce Vita

Favro, who holds degrees in commercial art, Etruscology and Roman architectural history, has been captivated by Roman architecture for quite some time. She has traveled to every corner of the Roman Empire, from Algeria to Germany to Lebanon, and written several books on the subject matter as well as worked on a long list of digital research projects that explore the ancient world. After authoring “The Urban Image of Augustan Rome,” Favro launched a digital research project that aims to uncover the truth behind Augustus’s famous declaration.

“I have worked on digital projects for a long time. With technology, I can be more experimental and adventurous in my own research,” said Favro. “It is also a way to help fund my doctoral students because the grants you can get using digital technology are so much larger.”

A New Approach

“Many scholars have looked at Augustus’s claim from a political standpoint, as a metaphor for him transforming a republic into an empire. I wanted to see if Rome literally transformed under his rule,” Favro explained.

Scholars have also tended to study the transformation of individual buildings in Rome instead of studying the transformation of the city as a whole because they lack the data needed to do so. Using advanced modeling software, Favro reconstructed The City of the Seven Hills in its entirety and observed how it changed during the period Augustus was in power.

Building the Model

Working with her doctoral students Marie Saldana and Brian Sahotsky, Favro recreated Augustan Rome algorithmically using a technique known as procedural modeling.

“Procedural modeling is often used by urban designers to create contemporary cities, but it has not been widely used as a tool to reconstruct ancient cities,” she said.

The approach is based on rules for generating architectural forms. If Favro changes one rule, the model of Rome will automatically regenerate, saving time and energy. “The model is changing all the time, and that fluidity gives it an experimental aura. Rather than having one beautifully-rendered model that looks so good you never want to change it, you have a model that can easily be changed as new research takes place,” she explained.

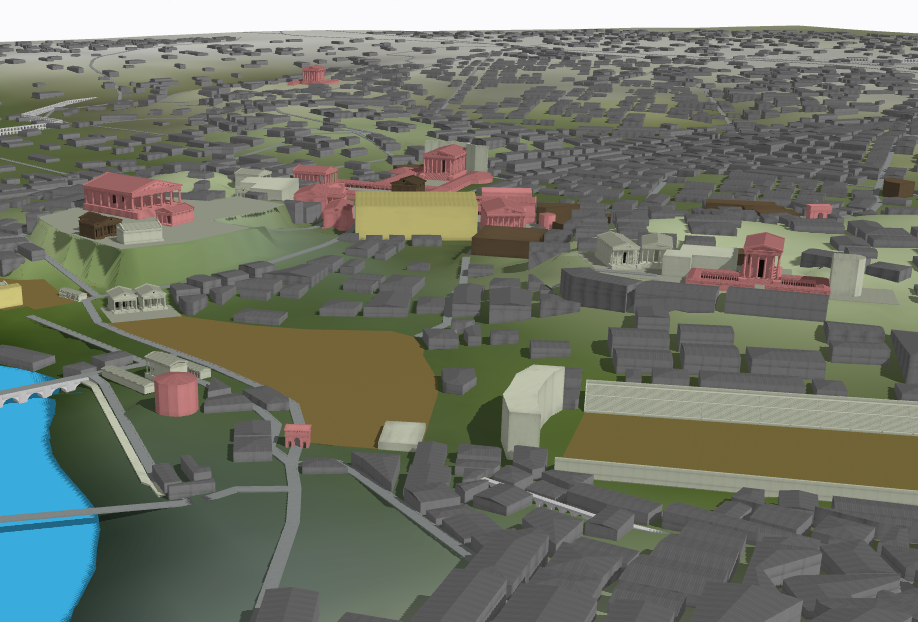

To further save on time, Favro used massing models instead of hyper-realistic models to construct the buildings, which involve a lot of hypothetical components and are highly labor-intensive. All of the buildings are color-coded: Marble buildings are pink, brick buildings are brown, and buildings under construction are yellow. Using a time slider available on the working site that Favro and her team have developed, people can travel from 44 BC to 14 AD and see how the city changed.

Experiential Technology

Similar to Google Maps, users can view Augustan Rome from above or from the street. “I am interested in experiential technology, in architecture as lived space. Instead of always studying ancient cities like Rome from above, I think it is important to go to the ground level and move through a city space,” said Favro. With modeling software, “I have control of the experience, the movement and the viewing angle. I can approximate the experience of what people saw in 44 BC!”

A Puzzling Observation

After carefully studying the model, Favro found that only a small proportion of the buildings in Augustan Rome were converted from brick to marble, and the marble buildings that were erected proved difficult to see in the cityscape.

“Given the literary descriptions and artwork, I thought these glittering marble temples on high would be very visible, but they were not.” she said. Favro has a theory to explain this puzzling observation.

An Illusion of Transformation

Just before Augustus came to power, the Carrara marble quarries on the northwest coast of Italy were opened, and the Roman world entered an era of relative peace, known as the Pax Romana. With the availability of local marble and absence of war, Rome’s first emperor was free to begin a massive construction project throughout the city.

Augustus commissioned several large marble structures, some of which took 40 years to complete. As a result, massive marble blocks were constantly being moved through the city, causing congestion in the streets. “Because they saw construction taking place constantly, I believe people really did think that Rome had been transformed into marble. But in reality, the city did not greatly transform.”

Marble-paved public spaces, which used to only be found in sacred temples and houses of the elite, were also added throughout the city. “Suddenly, everybody moving through the area could find themselves walking on marble, so they felt like they belonged to this more elevated status,” said Favro.

Due to the visibility and ubiquity of construction, the Romans were under the impression that the city had transformed, but it was mostly an illusion.

Moving Forward

In the future, Favro plans to continue refining this project. She will also continue to serve as the co-director of UCLA’s Experiential Technologies Center (ETC), a collaborative, interdisciplinary center that promotes experiential research in the digital age.

“The ETC is grant-driven so anybody on campus who has a grant and wants help with 3D modeling can partner with the ETC, and we will make software suggestions and direct them to experts,” she said. “We try to stimulate ongoing projects and new projects and push the envelope a little bit.”